邮箱 :news@@cgcvc.com

文章来源:AVCJ 发布日期:2019-11-20

Venture capital investors in China are turning their minds and manpower to the country’s nascent enterprise software opportunity, but the evolution curve is unlikely to be an exact match of the US

“Online traffic and e-commerce are the bright side of the moon that everyone can see.Enterprise software and related infrastructure comprise the dark side” – Wayne Shiong

Has the low-hanging fruit in China’s consumer internet space now been taken from the tree? While it is inadvisable to draw binary conclusions in a market so large and nuanced, many venture capital firms appear to be voting with their headcount. Teams that once focused on consumer opportunities are now being redirected towards business services, industry sources say. Sequoia Capital China is cited as one of the most prominent examples.

Xing Liu, a partner with the firm, observes that individual team members are never focused on certain sectors for early stage investments. “It is part of a dynamic process, evolving with the environment,” he explains. But the significance of the evolution is unmistakable and undeniable.

“After a decade of consumer internet development, more start-up founders are looking at ways to improve business services to deliver a better customer experience and greater efficiency,” Liu tells AVCJ. “As a result, VC and growth capital investors are spending more time on business technology. For the next 5-10 years, business technology will have many powerful applications in China, just like what has happened in the US.”

The US enterprise story started in the 1970s with Oracle, now a multi-billion-dollar enterprise, and continues with Zoom, Slack, and Zscaler, some of the biggest and best-performing IPOs this year. Meanwhile, UiPath, a robotic process automation specialist, represents the next generation. The company achieved a valuation of $7 billion on completing its Series D in April, up from $110 million 24 months ago.

Enterprise achieved traction in the US long before consumer, as evidenced by the $884 billion in proceeds from exits of VC-backed US enterprise start-ups since 1995, compared to $773 billion for consumer. It is only in the past decade that consumer has blossomed, with $512 billion in exits to $440 billion, according to S&P Capital IQ. Nevertheless, enterprise still outpaces consumer based on number of exits.

China’s journey is the complete opposite. “In the decade after 2000, there was only one major investment theme in China – consumer internet. When we got started in 2014, we were almost the only investor looking at SaaS [software-as-a- service]. We couldn’t even find a co-investor,” says Haiyan Wu, a partner at China Growth Capital. “But in the past two years, everyone in China has started looking at enterprise services.”

Going soft

The emergence of enterprise services is in part the result of technology-enabled disruption in the consumer space. Now most people enjoy the convenience of e-commerce and mobile payments, traditional businesses from supermarkets to hotels to banks must move online or risk becoming irrelevant. They need to upgrade their systems and start-ups are only too willing to help, creating opportunities across cloud services, big data analysis, artificial intelligence, and cybersecurity.

“Enterprises are more willing to pay for software and cloud computing services. A lot of enterprise services companies now generate over RMB100 million ($14.2 million) in annual revenue, which is a significant milestone,” Hesong Tang, founding partner of Xiang He Capital, told AVCJ earlier this year, anticipating a shift towards enterprise in his latest fund.

These changing dynamics are also proving beneficial for venture capital exits. Within the past 30 days, Qiming Venture Partners has sold two business services companies: cloud- based ID management platform IDsManager and cybersecurity services provider Chaitin Technology. In both instances, the buyer was Alibaba Group, which is keen to develop its own enterprise offering.

VCs embracing enterprise is a movement to the “dark side of the moon,” according to Wayne Shiong, another partner at China Growth Capital. “Online traffic and e-commerce are the bright side of the moon that everyone can see. Enterprise software and related infrastructure comprise the dark side, and now it’s time for the dark side to turn to the spotlight,” he explains.

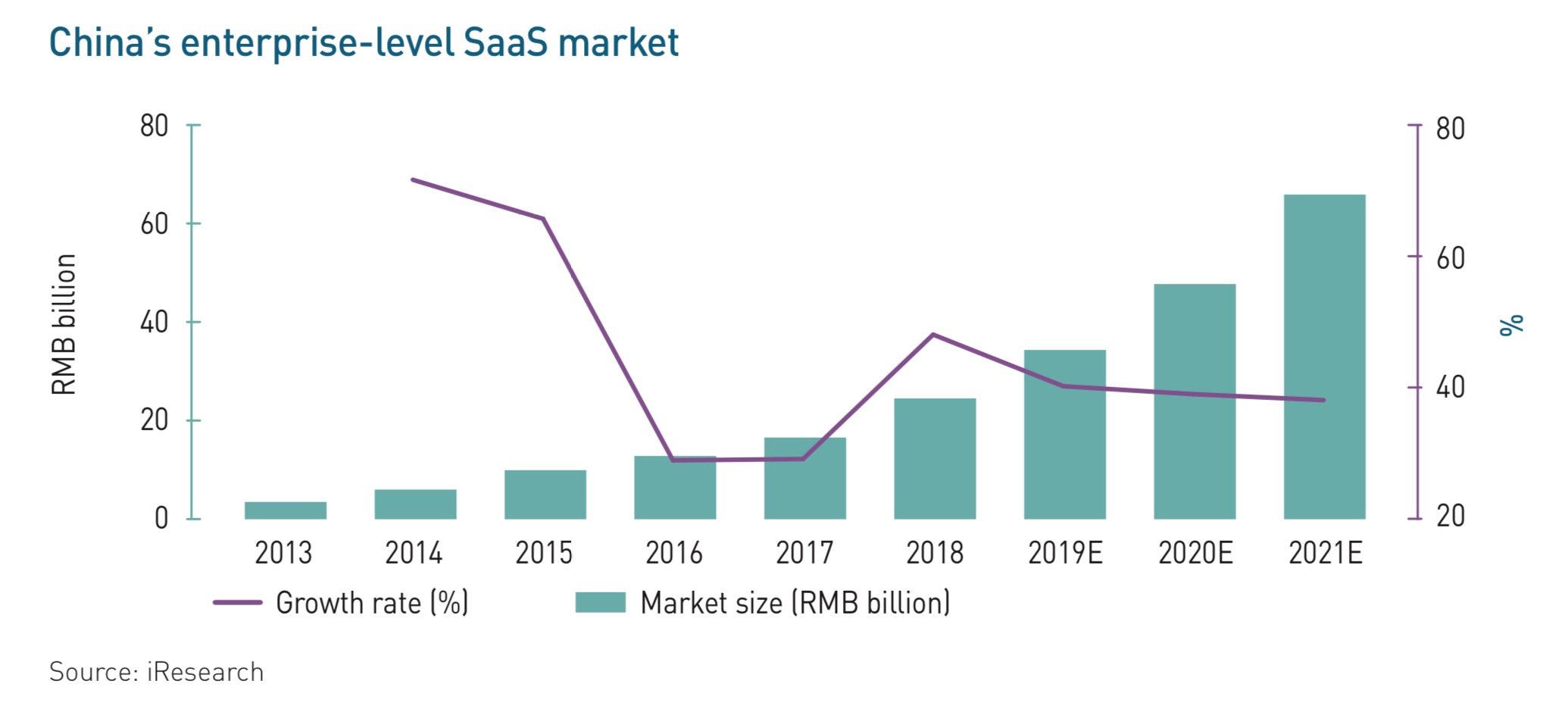

To many industry participants, software-as-a-service (SaaS) – specifically the migration of on- premises software to cloud-based solutions – is the biggest opportunity on the dark side. China’s enterprise-level SaaS market was worth RMB24.3 billion in 2018, a 48% year-on-year increase on 2017. IResearch Consulting projects it will reach RMB65.4 billion by 2021.

The SaaS segment’s most significant customer group is e-commerce platforms. Several recent deals illustrate this trend. In April, Tencent Holdings led a $116 million investment in China Youzan, which develops SaaS products, such as third-party payment solutions and customer engagement tools, for online and offline merchants. Jushuitan and Wangdiantong, two start-ups with a similar business model, have raised capital from the likes of TPG Capital, SoftBank Ventures and Sequoia Capital China.

Arguably, the global benchmark for SaaS providers is Salesforce, a customer relationship management (CRM) specialist with a market capitalization of $143 billion and $13.3 billion in annual revenue, a tenfold increase from 10 years ago. Approximately 90% of sales come from subscriptions with a gross margin of 80%.

The Chinese market simply isn’t mature enough for any local player to replicate this performance in the near term. The reality is most small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) gravitate towards free products, while large businesses favor customized solutions over standardized SaaS products.

CDP, a PE-backed software platform that focuses on human resources, claims to be the dominant player in China among SaaS-based payroll and benefits service providers by number of group customers served. Having initially concentrated on multinationals, the company says in its recently filed IPO prospectus that there is rising demand from local customers that “have grown at exceptional paces and have nationwide presence, both of which make it challenging to staff and manage their workforces.”

However, CDP’s costs are growing at a faster pace than its sales. In the first nine months of 2019, revenue rose 28% year-on-year to RMB674 million, while the net loss grew from RMB16.9 million to RMB157.5 million. Much of this is due to additional hiring and other expenses tied to growth that is anticipated but perhaps not yet sustainable.

“SaaS is very popular in US, but if we copy it to China taking a time machine approach - assuming what happened to US will happen to China – the effectiveness will only be 50% today,” says Erhai Liu, founding partner at Joy Capital. “Sometimes, a whole sector completely dies out. You have seen the upsurge of internet financing, peer to peer lending, right? Now it’s all gone. Investments in Taobao-branded products, in blogs, or in umbrella sharing, they are all back to zero.”

Enterprise plus

In Liu’s opinion, SaaS must be combined with offline operational support to create value. VC-backed Smart Fabric is a case in point. The company started out as a software provider to China’s textile industry but soon pivoted to become manager of a weaving and dyeing operation that comprises 2,000 small-scale manufacturers. It collects orders from overseas customers, breaks them down into different procedures, and delegates production to a factory with the appropriate machinery. The software that holds the network together is distributed for free; Smart Fabric makes its money from sales of textiles.

“It’s so difficult to make customers pay for software. In our network, all manufacturers get access to new orders and new revenues, that’s why they join,” Charles Fu, Smart Fabric’s founder, tells AVCJ.

This view is echoed by Wei Zhou, founder of China Creation Ventures (CCV). “If your solution improves an enterprise’s efficiency from 80% to 85%, it’s hard to make money. What we invest in is solutions that empower enterprises from zero to one,” he says. “In US, it might work well as a purely online software company. But the largest opportunity in China is industry digitalization – online solutions combined with offline operations – that gives enterprises a new ability, or an immediate new source of income.”

Earlier this year, CCV led an investment in Yunhu Technology, a medical testing logistics business. The company operates a cold chain logistics system that transfers samples – typically blood and urine – to 150,000 labs across 22 provinces. It covers a patient population of more than one million. The company also has a SaaS platform through which test results and analysis can be uploaded to the cloud and shared with patients.

“Without Yunhu, patients must go to hospitals for these tests – that is the status quo in China,” Zhou explains. “Yunhu help them retain customers and earn new revenues. These small clinics are therefore highly dependent on service providers.”

He describes such operators – whether clinics, hotels or restaurants – as the “forgotten half” of China. Just as Pinduoduo’s success is built on reaching out to underserved consumers in lower- tier cities, business services providers must find ways to access different layers of the market.

“Why do you have [Indian hotel platform] Oyo in China so many years after Ctrip and Expedia arrived?” Zhou adds. “It’s because small hotels appear on page 20 of a web search. Oyo has grouped them under a unified brand. That brand power gives them high visibility and low cost for traffic.”

Seeking sustainability

Indeed, the size of the enterprise opportunity has attracted some start-ups from the consumer space. Terminus, an Everbright incubated internet of things (IoT) solutions provider for enterprises, crossed the $1 billion threshold in August following a RMB2 billion funding round. However, the company started as a consumer-facing smart door lock manufacturer. According to Victor Ai, CEO of Terminus, the biggest difference between consumer and enterprise is the pace of growth.

“In the business sector, barriers are built over a long period of time, while in consumer it’s possible to be an overnight success. For example, if you run a ride-hailing app and offer free rides to acquire customers, you can accumulate 10 million daily active users in one week. But if you on business customers, charging an annual subscription fee.

Enterprise-facing start-ups tend to a have a clearer path to profit than their consumer brethren – relying on subscriptions rather than advertising – because they cannot expect to accumulate a large enough user base to generate a return on traffic. However, CCV’s Zhou argues that doesn’t necessarily lead to one adopting high cash-burn business models and the other not. Some consumer-facing start-ups are sustainable while Yunhu, for example, is still spending heavily to win market share among small clinics.

But there is one difference between enterprise and consumer that does ring true, according to Shiong of China Growth Capital: consumer-facing start-ups return to the well regularly and drink deeply, which might mean a VC investor that started with a 20% stake is diluted to 7% by Series B. Enterprise players tend to be more disciplined – perhaps even turning down money. “Sometimes, we want to invest more, in exchange for more shares, but the founder says no,” Shiong says.